Vectorman/Development

From Sega Retro

- Back to: Vectorman.

Development

After witnessing the 1989 demo Megademo by the demoscene group RSI - one of many demos featuring "vector balls" (in which plain spherical sprites are animated to give the appearance of three-dimensional depth) - BlueSky Software programmer Karl Robillard was particularly inspired by the demo's creation of human-like characters through such limited technology and attempted to get the same technology running on Sega's then-new Mega Drive hardware. With fellow programmer Rich Karpp, a small team at BlueSky threw together some similar animations as basic animation tests. Assured that Sega's new machine could pull off "vector balls" and still provide fun gameplay, Robillard set to programming his own vector balls engine for use in a proper pitch to BlueSky's management; the team points to this demo as the true inception for the VectorMan character.

| “ | Originally Karl and some of the others had devised a system to do actual 3D on the Sega Genesis, and they started with an animation of some 3D balls. This was actual 3D computing — on a Genesis. I saw the demo in Karl’s office back in ’93. They quickly realized there wasn’t much to be done with the original 3D ball tech because you couldn’t get it to run in a gameplay situation.”, adding “This was all before the ‘Ballz’ game came out. That game sorta proved the unworkability of the concept.

|

„ |

BlueSky's art director, Dana Christianson, overheard some of the team discussing possibilities for using the technology for different gameplay mechanics, and soon called for a meeting with BlueSky designers Mark Lorenzen and Jason Weesner. The latter formally proposed turning the popular demo into a video game, and management approved. The team was soon joined by artist and designer Mark Lorenzen, who along with Karpp convinced BlueSky's already-impressed management to show one of their early demos to Sega of America. Sega was just as impressed, and greenlit Vectorman for proper development. At the time, Nintendo's upcoming Donkey Kong Country was being heavily marketed, with its pre-rendered graphics taking center stage; particularly, the advertisements stated that such technology and animation were impossible on the Mega Drive. Sega of America saw Vectorman as one of their best opportunities to counter Donkey Kong Country's hype with an impressive technology of their own.

| “ | I intentionally stayed out of the process. I went into a meeting room one day and Jason Weesner was going on and on about a storyline which was based off of “The Running Man”, with the whole TV show aspect. On the spur of the moment I asked a friend of mine, Patrick Brogan, to write up some new storyline ideas. I think it was overnight, or, at most, over a weekend. Patrick came up with 8-to-10 new ideas. Rich picked the one he liked and we went with it. | „ |

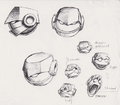

Electronic musician Jon Holland was soon brought onboard, and he, Lorezen, Karpp, and Weesner spent the next few weeks formulating ideas for what would eventually become Vectorman. Between listening to music, watching anime, and playing imported Japanese games for inspiration, these creative meetings were where much of the gameplay was conceptualized: a side-scrolling run-and-gun with elements of action platformers. However, the game's style had still yet to be finalized. According to Weesner, "Mark, Rich, and I wanted something edgy, contemporary, and geared towards a hipper audience than previous BlueSky games." Vectorman's protagonist began as a simple cartoon-like character named Shakespeare, boasting large eyes and a big nose, although this design was quickly rejected for being "too cute". Still, Lorenzen was beginning to become acquainted with delivering human expressiveness through the game's unique sphere-rendering technology (particularly in terms of shading individual spheres to better convey depth and realism), and ended up filling up two development sketchbooks with concept artwork and preliminary sketches.

Vectorman was designed around advanced graphical effects from the very beginning, and much of the game's development reflected the team's attempt to fully use its unique technology to the fullest. Enemies and bosses were created with sphere-based designs, and stage layouts were conceptualized which would further showcase BlueSky Software's programming skill.

Development material

Development diary written by animator Marty Davis.

Earlier sketchbook produced by designer Mark Lorenzen.

Later sketchbook produced by designer Mark Lorenzen.

Tech demo created for the game's pitch.[1]

Concept artwork

A scrapped swamp stage which appeared in Vectorman 2.

A scrapped swamp stage which appeared in Vectorman 2.

References

| Vectorman | |

|---|---|

|

Main page | Maps | Downloadable content | Changelog | Hidden content | Development | Magazine articles | Video coverage | Reception | Promotional material | Region coding | Technical information | Bootlegs

| |